"The blues, contrary to popular conception, are not always concerned with love, razors, dice, and death," Richard Wright wrote in 1941, in the liner notes to a new album of 78 rpm records. "Southern Exposure contains the blues, the wailing blues, the moaning blues, the laughing-crying blues, the sad-happy blues. But it contains also the fighting blues . . ."

Southern Exposure was the third album by Josh White, a young singer who was then staking out a unique position in American music: he was the only musician ever to make a name for himself singing political blues. Oddly, he made no claim to uniqueness; like Wright, he argued that the blues was by its nature a protest music, and decades of writers on the subject would concur. They always pointed, though, to veiled verses like "You don’t know my mind/ When you see me laughing, I’m laughing just to keep from crying." What Josh was singing was something quite different: a repertoire of blues about current events, written from a strong left-wing perspective. Some of the other blues artists who became caught up in the folk revival recorded similar pieces (Big Bill Broonzy’s "Black, Brown and White" and Leadbelly’s "Bourgeois Blues" are the most successful examples), but only Josh made it the centerpiece of his work.

In 1941, Josh White was 27 and had already lived out two previous musical careers. He had spent his childhood traveling around the South as "lead boy" for blind blues and gospel singers, making his first recordings at age 14 with the streetcorner evangelist Blind Joe Taggart. Then, in the early 1930s, he had settled in Harlem and became a solo artist, his records influencing a generation of players in the southeastern states (both Blind Boy Fuller and John Jackson covered his songs and guitar arrangements). These early recordings were pretty standard blues and gospel fare, though his guitar work was already outstanding and he was the only artist to have simultaneous success in the sacred and secular markets, recording gospel under his own name and blues as "Pinewood Tom." Only one of his 1930s records hinted at his future direction: in 1936 he put out "No More Ball and Chain" backed with "Silicosis Is Killin’ Me," two songs by a populist country songwriter, Bob Miller. Miller was a link between what was then called "hillbilly" music and the progressive New York scene, working with the Appalachian ballad singer and union organizer Aunt Molly Jackson and later the Almanac Singers, but his collaboration with Josh was brief. They might have done more work together, but, shortly after making the record, Josh cut his right hand so severely that he was unable to play for the next four years.

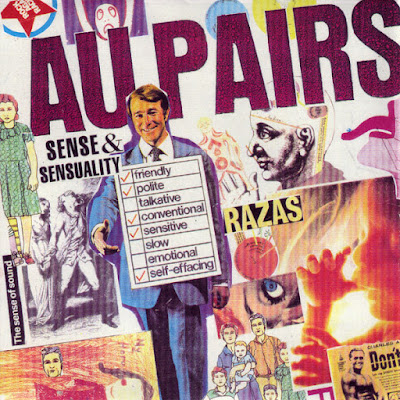

It was with the Almanacs that he first recorded for Keynote Records, an outgrowth of New Masses magazine, and in 1941 the label released his most influential album of the period, Southern Exposure: An Album of Jim Crow Blues. This time, the songs were all original compositions, collaborations between Josh and the Harlem Renaissance poet Waring Cuney. It was the first full-fledged Civil Rights record album, and there would never be another with so much popularity or impact. The title song gives an idea; written to the tune of "Careless Love," it was the lament of a Southern sharecropper:

Well, I work all the week in the blazin’ sun, (3x)

Can’t buy my shoes, Lord, when my payday comes.

I ain’t treated no better than a mountian goat, (3x)

Boss takes my crop and the poll takes my vote.

The rest of the material, most of it in a straightforward 12-bar blues framework, included "Jim Crow Train," Bad Housing Blues," and "Defense Factory Blues." The latter was typical, a hard-hitting attack on wartime factory segregation with lines like, "I’ll tell you one thing, that bossman ain’t my friend/ If he was, he’d give me some democracy to defend." Harlem’s main newspaper, the Amsterdam News, devoted two articles to the album’s release, rating it as a work that "no record library should be without" and emphasizing the painful familiarity of the subject matter: "All of you know the guy who ëwent to the defense factory trying to find some work to do . . .’; and over there on 133d St. and Park Ave., and down in Mississippi and out in Minnesota, we all have a brother or a sister or a cousin who can wail: ëwoke up this mornin’ rain water in my bed. . . . There ain’t no reason I should live this way. . . I’ve lost my job, can’t even get on the WPA.’"

(Thanks to Elijah Wald, Living Blues magazine, for the information.)

(224 kbps, front cover included)